The Smokestack Effect

The Smokestack Effect was a months-long investigative series into air pollution at every K-12 school in the United States — roughly, 130,00 — published by USA Today in 2008.

I served as the graphics editor, project manager, one of the story editors, and editor for the videos and other multimedia content.

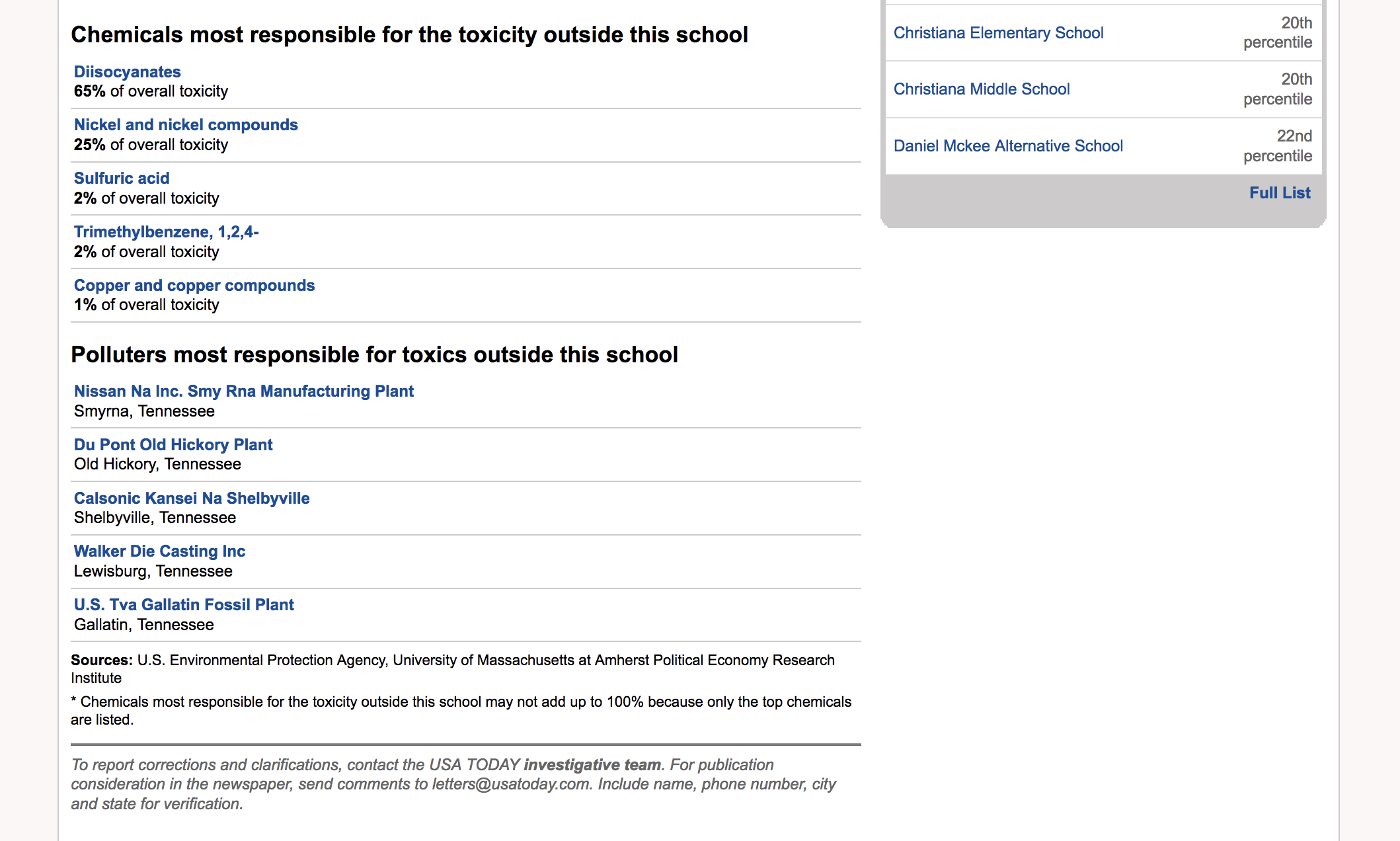

The centerpiece of the project was a data tool that parents, employees, politicians, and other stakeholders used to look up the air pollution at a given school. Each school’s pollution level was rated and placed on a scale relative to the other schools to provide comparisons. The tool showed the chemicals in the air, some of the possible pollution sources, and other resources.

The project also included several articles, basic information graphics, documentary videos, and photography.

The bulk of the raw data came from the EPA. We also worked with our partners at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland to install air quality sensors at 95 schools, making this one of the first uses of sensor technology to aid in reporting by a major media outlet.

At the time, this was the most extensive data-driven investigation and most advanced data model ever published by USA Today.

A few years after publication, USA Today retired its CMS, and sadly, this project did not survive. Millions of people used the tool during its lifetime, and our work received several major awards, including the Casey Medal, the Phillip Meyer Award (IRE), and the John B. Oakes Award from Columbia University, among others.

Read more about the project, including the methodology, below.

Methodology

Children are uniquely susceptible to the dangers posed by many sorts of toxic chemicals because they breathe more deeply than adults, and because their bodies are still developing. That's why USA Today worked with researchers and scientists at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and the University of Maryland in College Park to analyze exposure to industrial pollution at schools across the nation. The goal: To determine what sort of toxic chemicals children breathe when they go to school.

Schools List

USA Today gathered information on about 127,800 public and private schools from the National Center for Education Statistics and more than two dozen state education agencies. While we attempted to make the list as comprehensive as possible, it may not include some recently opened buildings. It also includes some schools that have closed since 2005. We also excluded some schools whose locations we could not map.

Toxicity Assessments

Toxicity assessments for each school are based on emissions data collected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as part of its Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) program. More than 20,000 industrial and government facilities are required to tell the agency about their emissions of hundreds of chemicals that are known to harm humans or the environment. Most facilities do not measure their emissions; rather, their reports to the TRI are estimates. It is difficult to verify the accuracy of those estimates, but some critics have complained that TRI reports generally understate emissions. Generally, only large industrial and government facilities are required to report to the TRI, meaning there are many other potential sources of pollution that are not included in the agency's data. As a result, those sources also are not included in toxicity assessments for schools.

To assess how those emissions affect the air outside nearby schools, USA Today partnered with researchers from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst's Political Economy Research Institute. After more than two years of effort, the researchers obtained data from an EPA model known as the Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators, which scores chemicals based on their potential danger. The model also uses information about industrial facilities — such as the height of smokestacks and the way each chemical disperses in the air — to estimate where concentrations of the chemicals they release will be highest. The model allows the EPA to assess pollution's impact on every square kilometer of the nation, and the agency uses that information to help identify potential problem spots.

The University of Massachusetts researchers used those findings to produce lists of chemicals that contributed to air toxicity at each of the nation's 127,800 schools in 2005, the most recent year for which the EPA has completed its model. With the help of University of Massachusetts researchers and other experts, and after consulting with the EPA, USA Today used those records to create three measures of a school's exposure to industrial toxics:

Overall toxicity: This is the primary measure of toxicity from industrial pollution outside a school. It reflects both the concentration of chemicals the EPA's model shows impacted the school in 2005, as well as the potential harm associated with those chemicals. That measurement is ranked against each of the other 127,800 schools for which USA Today developed toxicity information, and is displayed as a percentile. For example, if you see a school whose overall toxicity shows up in the second percentile, you'll know only 1% of the nation's schools had higher toxicity levels.

Exposure to cancer-causing chemicals: This ranking is similar to the overall toxicity measure, but includes only those chemicals known or thought to cause cancer. The measure shows how one school ranks relative to all of the nation's other schools.

Exposure to other toxic chemicals: This ranking shows the potential severity of exposure to chemicals that do not cause cancer. For each chemical thought to cause health problems other than cancer, EPA's reference concentration (the agency's exposure threshold) was used for comparison. In other words, the higher a school ranks on this scale, the more likely it is that non-carcinogens could exceed that threshold.

Limitations of the Model

Because these measures are based on a model and estimates of emissions, they are subject to some limitations. For example, the model makes certain assumptions about topography, the height of smokestacks, and the toxicity of certain chemicals, any of which could influence the assessment of toxicity in a particular location. In some cases, the EPA model appeared to underestimate exposure to toxic chemicals. In others, it appeared to overstate it. Also, the model is not meant to assess risk—your chances of getting sick.

Because it is based on reports from 2005 and includes only some potential sources of pollution, the model may not fully reflect the current situation at each school. For example, some facilities have closed since 2005, and others have opened. Also, large industrial sites account for only a fraction of the nation's toxic air pollution. The EPA estimates that in 2002, cars, smaller businesses, and other sources accounted for 85% of the toxic chemicals in the nation's air.

Monitoring

Under the guidance of scientists from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland School of Public Health, USA Today monitored air quality near 95 public and private schools throughout the nation. Monitors were placed mainly—but not exclusively—near schools that the EPA model suggests face higher exposure to industrial pollution.

To make the most complete assessment possible, three main types of monitors were used, depending on the types of chemicals the model suggested would be present:

Badges: Simple badge-like monitors were placed near 95 schools in 30 states. These badges collect a class of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds. A similar badge was also used to detect ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen, near 23 schools. The badges remained in place for four days to a week before being sent to the University of Maryland for analysis.

Active monitors: Some chemicals, such as metals, cannot be picked up on badge monitors. To measure these, USA Today employees set up pumps to collect samples of metals near 17 schools and polycyclic aromatic compounds near 23 schools. At these schools, air was monitored for 72 to 96 hours.

Filters that collected metals were analyzed by Johns Hopkins University.

Other samples were analyzed by the University of Maryland.

Ultraviolet monitors: Some chemicals cannot be easily measured using badges or active samplers. To detect these, an ultraviolet detection system (made by Cerex Monitoring Solutions) was used to conduct additional monitoring near eight schools in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas.

This monitor delivers its findings in real time and does not require laboratory analysis.

The monitoring work was conducted by employees of USA Today and other affiliated newspapers and television stations. In each case, an effort was made to place the monitors within 100 yards of a school, although in some cases, a few had to be placed slightly farther away.

Scientists at the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins analyzed each sample and interpreted the results.

Because USA Today was only able to monitor for a short period of time, the findings may not fully reflect the extent of long-term exposure to pollutants at any particular location. For example, changes in wind direction or activity levels at a particular industrial facility can significantly influence the concentration levels near a school on any given day.